Public sculpture is one of the most dynamic and innovative ways to create links between social, economic, cultural and political communities within cities. Sparking conversation, a sense of community and historical recognition, public sculpture is one of the cornerstones of London’s architectural landscape. In honour of Sculpture Week London 2022, which began on Monday 12 September, The Wick highlights ten sculptures that mean the most to us.

Henry Moore, The Arch, 1979-80.

Situated in Kensington Gardens on the North bank of the Long Water, Henry Moore’s six-metre-high sculpture aptly entitled “The Arch” is one of the garden’s most recognisable features. Made from seven travertine stones sourced from northern Italy and weighing a total of 37 tonnes, “The Arch” was personally donated by Moore to the gardens. However, due to its weight and shape, the sculpture was found to be unstable in 1996 and was subsequently dismantled and underwent a 16-year long restoration process until it was finally reinstalled in its rightful place in 2012.

Situated in Kensington Gardens on the North bank of the Long Water, Henry Moore’s six-metre-high sculpture aptly entitled “The Arch” is one of the garden’s most recognisable features. Made from seven travertine stones sourced from northern Italy and weighing a total of 37 tonnes, “The Arch” was personally donated by Moore to the gardens. However, due to its weight and shape, the sculpture was found to be unstable in 1996 and was subsequently dismantled and underwent a 16-year long restoration process until it was finally reinstalled in its rightful place in 2012.

Conrad Shawcross, Bicameral, 2019.

Integrated into the Chelsea Barracks – a recent redevelopment of former British Army barracks into a block of modern residences and townhouses in the heart of London – is a sculpture by British sculptor Conrad Shawcross. Entitled “Bicameral” the tree-like sculpture reflects the rich botanical history of the surrounding districts of Belgravia, Chelsea and Pimlico. Known to represent life, growth, wisdom and prosperity, the sculpture also harks back to the materials used to build the original barracks, whilst looking towards the prosperous and ever-changing landscape of London’s architecture.

Integrated into the Chelsea Barracks – a recent redevelopment of former British Army barracks into a block of modern residences and townhouses in the heart of London – is a sculpture by British sculptor Conrad Shawcross. Entitled “Bicameral” the tree-like sculpture reflects the rich botanical history of the surrounding districts of Belgravia, Chelsea and Pimlico. Known to represent life, growth, wisdom and prosperity, the sculpture also harks back to the materials used to build the original barracks, whilst looking towards the prosperous and ever-changing landscape of London’s architecture.

Lynn Chadwick, King and Queen, 1990.

Lynn Chadwick’s sculpture situated atop the entrance façade of Fortnum & Mason is one of London’s hidden sculptural gems. Entitled “King and Queen” the sculpture portrays a pair of figures created from interlocking triangular and square shapes looking out onto the busy London landscape. Created in 1990, the sculpture was initially installed as a temporary feature in 2016 as part of an exhibition held in Fortnum’s at the time. The couple appears to have secured their ‘throne’ and have since become one of the most beloved public installations in the city.

Lynn Chadwick’s sculpture situated atop the entrance façade of Fortnum & Mason is one of London’s hidden sculptural gems. Entitled “King and Queen” the sculpture portrays a pair of figures created from interlocking triangular and square shapes looking out onto the busy London landscape. Created in 1990, the sculpture was initially installed as a temporary feature in 2016 as part of an exhibition held in Fortnum’s at the time. The couple appears to have secured their ‘throne’ and have since become one of the most beloved public installations in the city.

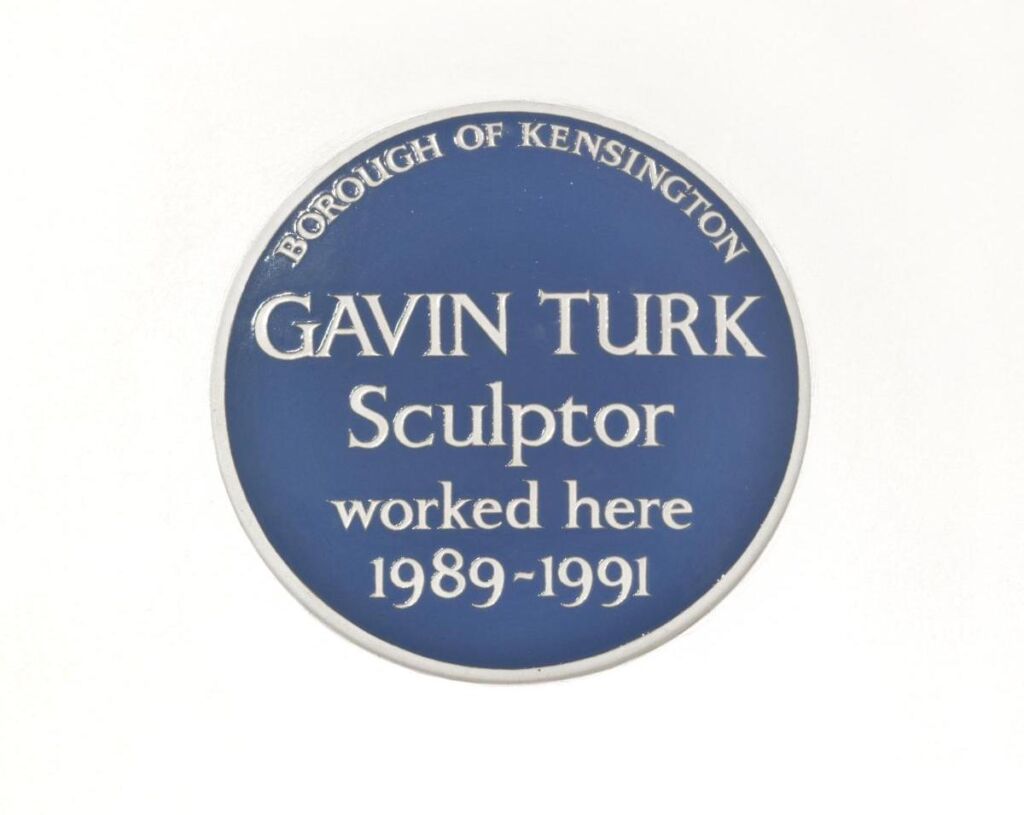

Gavin Turk, Cavey, 1991-7.

British sculptor Gavin Turk is known for his playful reinventions of objects from everyday life that comment on issues surrounding authenticity and identity. Continuing with this theme, his sculpture “Cavey” reimagines the iconic blue plaques that adorn buildings all over London to commemorate links between buildings and the people that lived or worked in them with his own name and profession. Created during his time at the Royal College of Art, the plaque continues to commemorate life and uniquely marks the presence of the artist through absence and history.

British sculptor Gavin Turk is known for his playful reinventions of objects from everyday life that comment on issues surrounding authenticity and identity. Continuing with this theme, his sculpture “Cavey” reimagines the iconic blue plaques that adorn buildings all over London to commemorate links between buildings and the people that lived or worked in them with his own name and profession. Created during his time at the Royal College of Art, the plaque continues to commemorate life and uniquely marks the presence of the artist through absence and history.

Yoshitomo Nara, Peace Head, 2021.

This summer iconic Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara teamed up with Pace Gallery for a brand-new installation in the recently renovated Hanover Square opposite the gallery’s headquarters and also marks the first time Nara presented a work of public sculpture in the UK. “Peace Head” brings one of Nara’s playful pop characters to life, an element that is emphasised by a strong sense of physicality and materiality realised in the visible imprints of Nara’s sculpting process as he pulled, smoothed or smashed the clay into shape.

This summer iconic Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara teamed up with Pace Gallery for a brand-new installation in the recently renovated Hanover Square opposite the gallery’s headquarters and also marks the first time Nara presented a work of public sculpture in the UK. “Peace Head” brings one of Nara’s playful pop characters to life, an element that is emphasised by a strong sense of physicality and materiality realised in the visible imprints of Nara’s sculpting process as he pulled, smoothed or smashed the clay into shape.

Antony Gormley, Cinch, 2013.

Another hidden gem in the centre of London is Antony Gormley’s first solid stainless-steel sculpture “Cinch” on the north facade of the historic shopping corridor, The Burlington Arcade. Perched high on a parapet and silhouetted against the sky, the reflective patina of “Cinch” reacts to figures walking by and the changes in natural light, which conveys the idea of a human as a work in progress, ever-changing. Blink and you might miss it.

Another hidden gem in the centre of London is Antony Gormley’s first solid stainless-steel sculpture “Cinch” on the north facade of the historic shopping corridor, The Burlington Arcade. Perched high on a parapet and silhouetted against the sky, the reflective patina of “Cinch” reacts to figures walking by and the changes in natural light, which conveys the idea of a human as a work in progress, ever-changing. Blink and you might miss it.

Yinka Shonibare, Wind Sculpture, 2014.

Commissioned by HS projects, Yinka Shonibare’s permanent sculpture “Wind Sculpture” takes the form of a colourful ship’s sail and explores the notion of movement through nature. Positioned at Howick Place in London, the sculpture harks back to the location’s namesake after Viscount Howick, who was one of the key figures of the Reform Act in 1832, which fought for Catholic emancipation and the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Utilising his signature bold colours and patterns that have become synonymous with African identity, Shonibare’s sculpture is a poignant reminder of Britain’s history.

Commissioned by HS projects, Yinka Shonibare’s permanent sculpture “Wind Sculpture” takes the form of a colourful ship’s sail and explores the notion of movement through nature. Positioned at Howick Place in London, the sculpture harks back to the location’s namesake after Viscount Howick, who was one of the key figures of the Reform Act in 1832, which fought for Catholic emancipation and the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Utilising his signature bold colours and patterns that have become synonymous with African identity, Shonibare’s sculpture is a poignant reminder of Britain’s history.

Eva Rothschild, My World and Your World, 2020.

As part of The King’s Cross Project – a programme that commissions art for buildings and public spaces to rejuvenate and bring attention to the King’s Cross area – Eva Rothschild created a colossal 16-metre tall sculpture that evokes links between the mechanical and natural world. She achieves this through her use of steel and the organic shape that might evoke an image of the branches of an inverted tree, a river basin, or a lightning bolt. Painted in the artist’s distinctive colour palette of black, purple, pink, green, orange and red, the stripes create an optical illusion for spectators that splits the sculpture into further parts.

As part of The King’s Cross Project – a programme that commissions art for buildings and public spaces to rejuvenate and bring attention to the King’s Cross area – Eva Rothschild created a colossal 16-metre tall sculpture that evokes links between the mechanical and natural world. She achieves this through her use of steel and the organic shape that might evoke an image of the branches of an inverted tree, a river basin, or a lightning bolt. Painted in the artist’s distinctive colour palette of black, purple, pink, green, orange and red, the stripes create an optical illusion for spectators that splits the sculpture into further parts.

Nick Hornby, “Muse Offcut #1,” 2017.

British sculptor Nick Hornby has always been known to push the envelope with figuration and art history. His series titled “Sculpture (1507-2017)” installed on the grounds of Glyndebourne Opera House, Lewes in 2017 is widely regarded as some of his most exciting. Using computer software, Hornby combines numerous silhouettes from canonical sculptures found in art history to create new three-dimensional sculptures that invite spectators to walk around them and interact with their ever-changing forms.

British sculptor Nick Hornby has always been known to push the envelope with figuration and art history. His series titled “Sculpture (1507-2017)” installed on the grounds of Glyndebourne Opera House, Lewes in 2017 is widely regarded as some of his most exciting. Using computer software, Hornby combines numerous silhouettes from canonical sculptures found in art history to create new three-dimensional sculptures that invite spectators to walk around them and interact with their ever-changing forms.

Marc Quinn, Alison Lapper Pregnant, 2005.

For the occasion of his coveted Fourth Plinth commission in Trafalgar Square, Marc Quinn decided to create something unconventional – the portrait of disabled artist Alison Lapper when she was eight months pregnant carved in white marble. Wanting to draw attention to issues surrounding conceptions idealised physical beauty as dictated by fifth century Greek sculpture, Quinn decided to create a new model of female heroism for the public to engage with. Glorifying Alison’s beauty, Quinn redefined beauty standards and rejected classical notions of femininity. Of the sculpture Lapper said, “I regard it as a modern tribute to femininity, disability and motherhood. It is so rare to see disability in everyday life – let alone naked, pregnant and proud.”

For the occasion of his coveted Fourth Plinth commission in Trafalgar Square, Marc Quinn decided to create something unconventional – the portrait of disabled artist Alison Lapper when she was eight months pregnant carved in white marble. Wanting to draw attention to issues surrounding conceptions idealised physical beauty as dictated by fifth century Greek sculpture, Quinn decided to create a new model of female heroism for the public to engage with. Glorifying Alison’s beauty, Quinn redefined beauty standards and rejected classical notions of femininity. Of the sculpture Lapper said, “I regard it as a modern tribute to femininity, disability and motherhood. It is so rare to see disability in everyday life – let alone naked, pregnant and proud.”

READ MORE