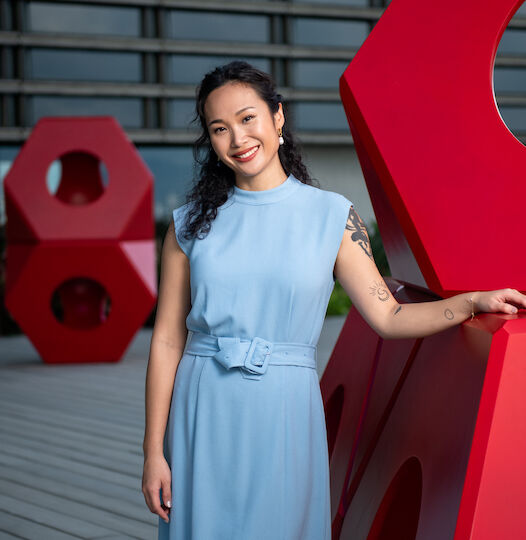

Interview Curator and collector Marcelle Joseph

She is also on the advisory board of Procreate Project, a London-based organisation devoted to supporting the professional development of contemporary artists who are also mothers, and collects artworks by female-identifying artists under the collecting partnership, GIRLPOWER Collection, and more generally as part of the Marcelle Joseph Collection.

Until 23 April, her collections are on public display for the first time in the UK in a travelling exhibition she co-curated at the Rugby Art Gallery & Museum.

THE WICK: Talk us through a typical Monday.

Marcelle Joseph: After either a morning yoga or spinning class, Mondays are an office day. As an independent curator, my office is in my home. I live quite peripatetically between two places in the UK – I divide up my week between being in London, running around to meetings with co-curators, studio visits with artists and seeing as much art in person, and being in Ascot behind my desk. Mondays are all about catching up on my emails, doing research for upcoming curatorial projects or checking out the next artist whose work I would like to acquire for either the GIRLPOWER Collection or my own collection. Mondays are also a time for reflection as I am on my own in Ascot as my husband is working in town and my children no longer live at home. After lunch, I try to spend some time outdoors. Luckily, I live near Swinley Forest and Windsor Great Park where there are excellent hiking trails, and forest bathing is one of my favourite things to do. Walking in nature is where I come up with my best ideas, whether it is the title of an upcoming exhibition or the lyric of a song I would like to use as an epigraph in an exhibition press release.

TW: Who is your personal Monday Muse?

MJ: As a curator whose academic specialisation is in feminist theory, I would have to choose the American gender theorist Judith Butler. I am reading a lot of her work for a 2023 exhibition I am co-curating with Becca Pelly-Fry at GIANT, a not-for-profit contemporary art space in the former Debenhams department store in Bournemouth. This exhibition will pair historic second-wave feminist artists with early-career contemporary artists. Like Butler, I am a big believer in the performative construction of gender identity, meaning that one’s learned performance of gendered behaviour such as femininity or masculinity is not natural but an act of sorts, a performance, one that is imposed upon us by normative heterosexuality.

TW: Are there any aspects of your life in law that influences your approach today and how did you pivot to being a curator?

MJ: As a trustee of Matt’s Gallery and Mimosa House, two London-based contemporary art spaces, I am using my skills as a former corporate lawyer on a daily basis. I sit on the financial committees of both institutions, given my skills gained from 11 years of reading and analysing financial statements before taking a corporate client public in an IPO. After over a decade of impossibly long hours and incessant corporate travel, I burned out on that lifestyle and also wanted to have children so I left the law. I have always been passionate about art as I took an Art History class at Cornell University as a lark with a friend and loved it so much, I ended up with a minor in Art History. After leaving my legal career, I went back to school to retrain, completing first a foundation course in Art Business at Christie’s London and later an MA in Art History at Birkbeck. In 2011, I set up Marcelle Joseph Projects. At first, it was very much DIY from finding a gallery to hire (you could do that in 2011 in Shoreditch – imagine!) to transporting the artwork from the artist’s studio to the gallery myself. Now, I only independently curate exhibitions for galleries and museums.

TW: What do you enjoy most about curation, and what makes for a brilliant exhibition?

MJ: The best bit of curating for me is working with living artists. I learn so much from the artists I work with as they are always at the forefront of the issues of the day. Studio visits are such important times to make new discoveries, whether it be a new artist or, more importantly, new lines of thought and enquiry. In terms of what makes a brilliant exhibition, it is a well-researched exhibition thematic and a group of cross-generational artists whose artworks are in lively dialogue and debate with each other in ways that the viewer had not already thought about or thought possible.

“The reason why I buy the work of predominately women artists is to explore my own subjectivity as a woman in this world.”