Interview Artist Sue Webster

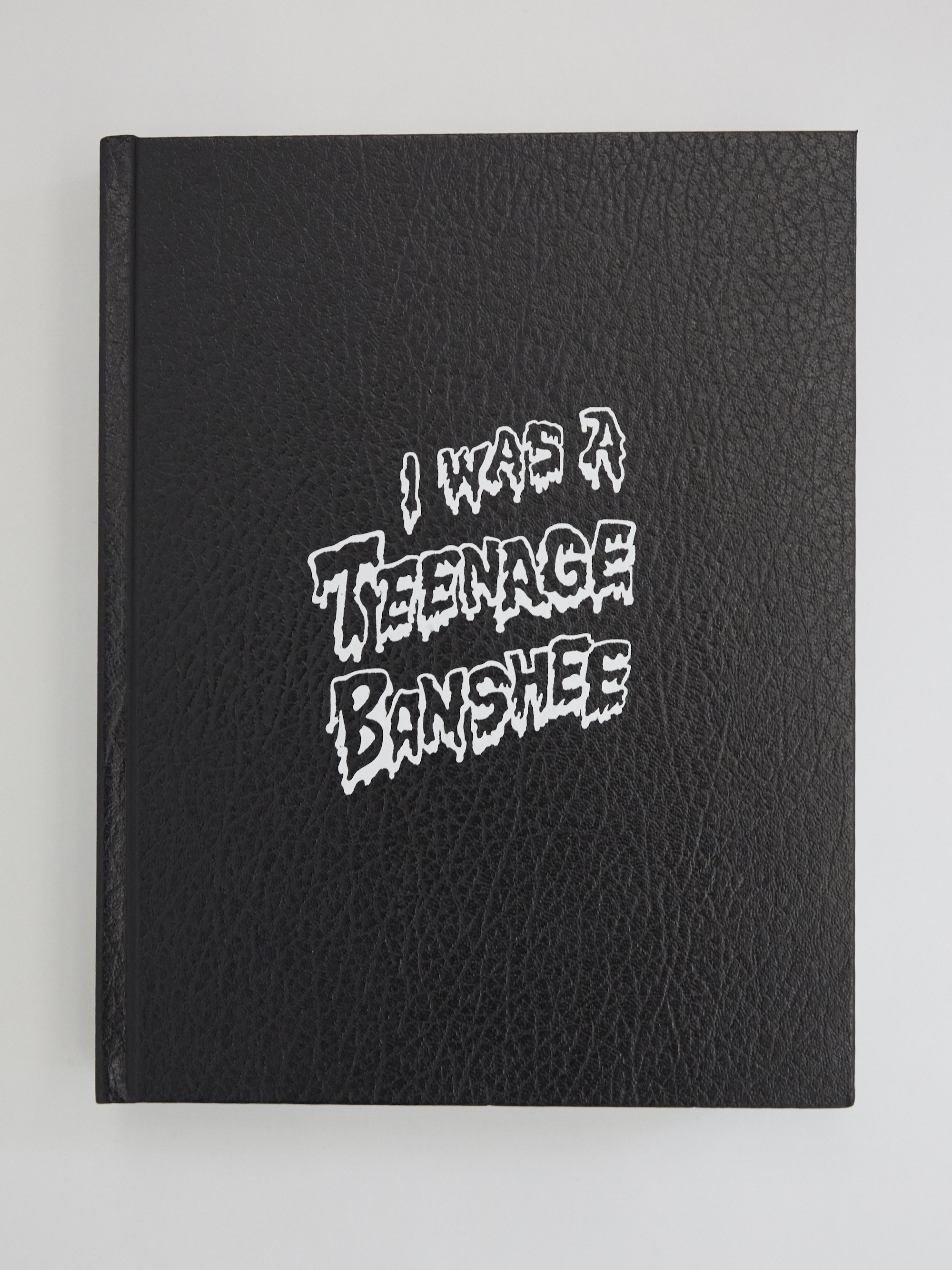

FULL LEATHER JACKETS, a collection of 18 customised leather jackets, pays tribute to Webster’s life-long appreciation of singer Siouxsie Sioux. It’s a theme she’s touched on before in her second biography I Was a Teenage Banshee (2019), which combines personal memoir with a visual narrative of her evolution as an artist.

During lockdown Webster regressed back to her teenage self when listening to Siouxsie and the Banshees helped guide her. Here she shares why she considers Siouxsie Sioux as an adopted mother figure and how becoming a mother herself has changed her.

THE WICK: Talk us through your typical Monday.

Sue Webster: I have an 18-month-old son, Spider-Ray, and weekends are all about him, so by Monday morning I’m usually clawing at the door to my studio to get back in and work on the ideas that have been brewing since Friday. I wake up most mornings usually between 6-7am, which is when Spider-Ray’s ready for action. It’s very painful during the winter months as I’m a big sleeper and find it difficult to justify getting out of bed in the dark. I’ll pick him up and put him into bed with me and switch Peppa Pig or something on the telly to try to occupy him while I crawl back under the covers until daylight creeps through the blackout blinds, then I feed him, bath and dress him. He’ll head off to nursery for 9am then I wander down the concrete staircase that leads like a labyrinth into the sanctuary that is my studio, my space, breathe a heavy sigh of relief and then that’s when all hell breaks loose.

TW: Light, rubbish and transformation are central to your work – how do you combine these?

SW: I’ve always been a skip-diver. Back in my art student days at Nottingham if you saw a pair of skinny legs dangling over the edge of the skip in the sculpture department car park, looking for a piece of treasure someone else had chucked away, that’d be me. That’s one advantage of pushing a 4-wheel drive baby buggy around town, I made sure I bought one that had a big enough luggage compartment underneath for carrying the shopping so I can pile it up with any bits of junk I find when roaming the street.

TW: You have written several books, how similar is the process of writing to making art?

CR:

They say that everyone has at least one book in them, and I wanted to test myself to see whether I had it in me. It was during a difficult period in my life, I was going through a major transition – I’d left the marital home and all of the security that comes with it, packed up my belongings, threw the keys through the letterbox and headed west. I holed up for a while in a Breaking Bad-style trailer in a field in Cornwall at the ends of the earth. I had a troubled adolescence that I had put in a box and closed the lid on, but I knew that in order to move forward I had to confront my teenage self, so I took a studio at Porthmeor Studios in St Ives overlooking the Atlantic and waited for it all to pour out.

Instead of staring at a blank canvas, you find yourself staring at a blank page or a computer screen – it’s just another way of unravelling your brain.

TW: What do you think is the biggest change the art world has seen in your 24-year career?

SW: I’ve seen first-hand how money chased after art and then watched as art chased after the money.

“The whole punk rock movement in England in the late Seventies felt like one of the first instances where women were given equal importance.”