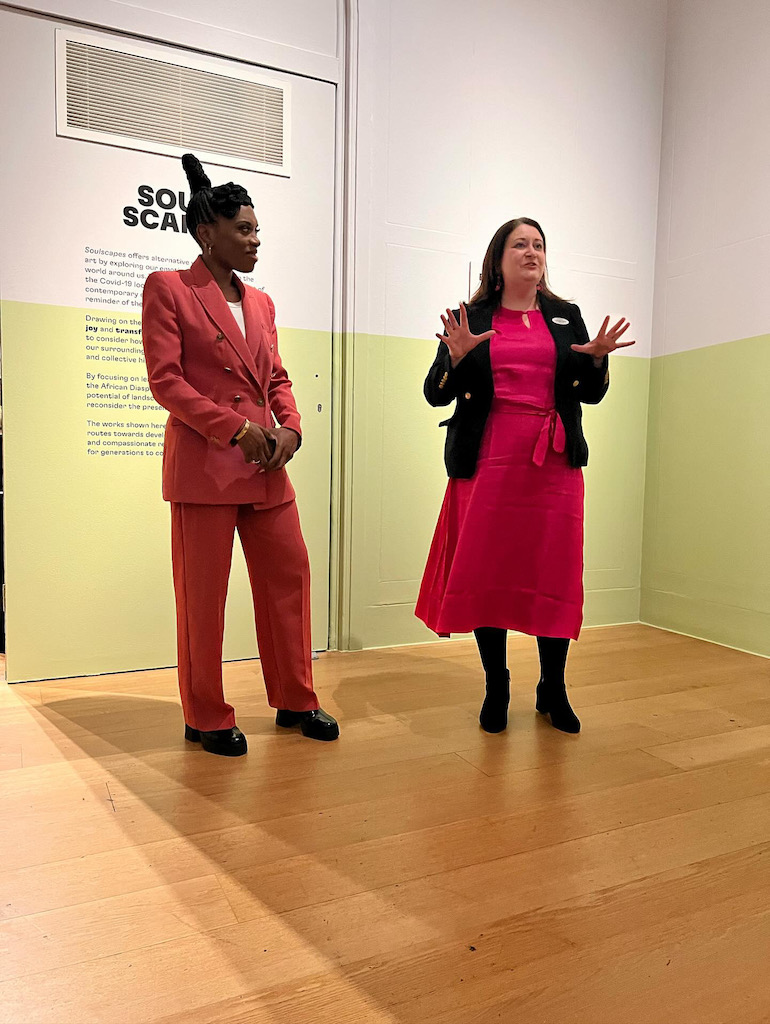

Interview curator and Black Cultural Archives director Lisa Anderson

As if this wasn’t enough, she has also developed an independent curatorial and arts consultancy practice, Lisa Anderson Arts Advisory, with a focus on artists from the African Diaspora, particularly in the UK, and she launched @blackbritishart in 2015 to celebrate and promote the breadth of their work.

Her latest brainchild is Soulscapes: African Diaspora Artists and the Natural World at Dulwich Picture Gallery, an exhibition that considers how people experience the land and how this connects with our sense of self and belonging.

She tells The Wick why she wants everyone to feel nourished by nature, how she powers up for the week ahead and reveals the Black feminists from British history that she most admires.

THE WICK: How does a typical Monday start for you?

Lisa Anderson: I start my day with a prayer, hot water, journalling, green smoothie preparation (kale, spinach, ginger, celery, broccoli, oat milk and banana) and low intensity exercise before reviewing plans, checking emails and social media, and touching base with line reports. I usually work from our headquarters at Black Cultural Archives, but as we’re closed to the public from Monday to Wednesday, I often take the opportunity to work from home on a Monday.

TW: What is your main goal at the Black Cultural Archives and is there an achievement that you’re particularly proud of?

LA:

The vision of Black Cultural Archives is to be the home of Black British history – to collect, preserve and celebrate the histories of people of African and Caribbean descent in order to inspire and give strength to individuals, communities and society. It exists to plug the gap of representation and knowledge of Black history in the midst of persistent racism. My goal is to secure BCA’s long term financial and organisational resilience to ensure it can help support the creation of a more just and equitable society. The UK needs and deserves its own version of the US’s Smithsonian or Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture – we urgently need a dedicated institution that can convene and strengthen scholarship for a more inclusive and authentic story of Britain that includes Black historical contributions beyond the history of Windrush Generation or the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

For us to attract the support we need, we need to speak more clearly about our work and impact, and attract wider audiences. People often tell me that since my leadership, BCA has increased its profile – whether it’s a result of our award-winning AR partnership with Snapchat, Royal Holloway University, the Great Day in Brixton photoshoot, our Challenging the Narrative: Black Resistance to Scientific Bias exhibition with Larry Achiampong and David Blandy or our CIRCA partnership for the 75th anniversary of WIndrush.

TW: You’ve described how your exhibition Soulscapes at Dulwich Picture Gallery this week “makes space for new versions of the world”. Can you tell us how, giving us a couple of examples of the artworks?

LA: There’s a throughline between my work at BCA, my commitment to social justice and my approach to art curation. My aim with Soulscapes is to leverage the radical imagination of these artists to help people contemplate a world where joy could be experienced more freely and equitably, where all people could feel a deep sense of belonging wherever they’ve rightfully chosen to make a home. This joy is perfectly expressed through Harold Offeh’s work showing Black figures lounging gracefully in picturesque natural surroundings, seemingly at one and in alignment with nature. It conveys the sense of ease and connection I wish that all people can experience.

TW: Is there a figure from Black British history that you were unaware of before you joined BCA whose story particularly struck you and that you feel deserves more attention?

LA: I’ve loved learning more about Black feminist history and how significant the [radical feminist and gay rights activist] Linda Bellos’ political journey has been, particularly in the context of Lambeth, [where she led the council for Labour in the 1980s]. Similarly, I also loved learning more about Mary Prince, the first Black woman to publish an autobiography of her experience of enslavement. She also wrote a letter to parliament, asking them to free all enslaved people in the Caribbean. By doing this, she was the first woman in Britain to petition Parliament. She died at the age of around 45 in the UK, which makes me determined to create as much impact during my life as possible.

“My aim with Soulscapes is to leverage the radical imagination of these artists to help people contemplate a world where joy could be experienced more freely and equitably…”