Interview South African Architect Sumayya Vally

Last year also saw Vally selected by the World Economic Forum to be one of its Young Global Leaders – a community of the world’s most promising artists, activists, and political leaders – and named on the TIME100 Next list as someone who will shape the future of architectural practice. Vally is committed to unearthing new dialogues searching for expression for hybrid identities and territory, particularly for African and Islamic conditions—both rooted and diasporic.

Amongst her many accolades, Vally recently joined the World Monuments Fund Board of Directors and alongside other projects is currently collaborating on the design of the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development in Monrovia, Liberia – the first presidential library dedicated to a female head of state, where she will oversee the scenography, pavilions, and exhibition spaces.

In terms of shaping and educating a new vision for architecture and design, Sumayya Vally is doing this next as part of the curatorial team for the first Islamic Arts Biennale, which opens today (January 23) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and runs until April 23. The first event of its kind, the new biennale will showcase the art and creativity of Islamic culture, past and present, and see Vally curate alongside architect Omniya Abdel Barr, archaeologist Saad Alrashid and the Smithsonian’s Julian Raby.

THE WICK: Who is your ultimate Monday Muse?

Sumayya Vally: In this tribe, we evoke women near and far – friends, ancestors and mythical figures – women who write, organise, imagine and build worlds into being. There are many, and many of those are unrecognised. Take the architect genius of the Ndebele women – women who craft ritual objects and build and adorn their own homes. The calling of their names invokes the calling of millions of errant, unrecognised, other architects the world over – past, present and future. They are Sarah Mguni, Martha Mtsweni Ndala, Rossinah and Esther Mahlangu, Maria Ntobela Mahlangu, Dinah Mahlangu, Johanna Mkwebani, Martina Maghlangu, Anna Msiza, Sara Mthimunye, Sara and Lisbeth, Pikinini and Sara Skosana, Anna Mahlangu, Letty Ngoma.

TW: Counterspace is your own practice. What prompted its formation?

SV:

I was born and raised in a small, previously apartheid township called Laudium, but I spent much of my childhood at my grandfather’s stores on Ntemi Piliso Street in the heart of Joburg. Many South Africans didn’t (or still don’t) have the opportunity to interact with worlds outside of their own – spaces were (and are still) very much segregated. I think that walking the streets in the city, especially walking to the Joburg library, let me into worlds that I wouldn’t have seen otherwise – and I’ve always had an interest in this, in finding and creating worlds, and seeing what I truly consider architecture – the fabric of the city – as interesting starting points from which to imagine new worlds. I always had this desire to work in the city and to have a practice that brings together different parts of the city into the same world. So, I think how architecture came to me is through this – through the city and through fiction.

Joburg is rough, gritty, ruthless and fast in the nicest possible ways and the meanest possible ways. It is burden and opportunity at the same time, at many different levels. Its tensions and its histories and legacies of segregation and exclusion means that at every turn there is work to do. But it is also a vastly and vibrantly creative world of inspiration (in the other disciplines, not in architecture). There is a sense of something other – other stories, other magic, other soul – that is waiting to be unlocked and translated into form.

I felt very deeply that there was a lack of response from architecture to what is actually happening in the city. Counterspace was born out of this dissatisfaction – out of a frustration with the complicity of the architectural profession and canon in my context, in perpetuating inherited and imposed narratives and forms.

I really wanted to make work that troubles and counters these constructed narratives about ‘lack’ on the African continent – I believe that here, in the fringes and the margins, we can find what truly Johannesburg and African design languages can look like, and I wanted to work with and for this idea. The rest is history.

TW: Which philosophies formed from growing up in Laudium in Johannesburg, and how do they continue to inform your work?

SV:

The power and necessity of community.

Negotiation, listening – finding the fact that architecture is in everyone, working with platforms and resources that we have access to, in the service of projects of difference, all present an opportunity to imagine the world differently.

Creating new platforms that function in entirely different ways through multiple various avenues is an opportunity. Take the Support Structures for Support Structures fellowship programme as an example – conceived in collaboration with Serpentine’s Civic Projects programme with the intent that year on year it will build and grow a deeper network of bodies of knowledge that are coming from places of difference, so that we can seed and see different pathways and other worlds.

TW: You have worked with the Serpentine and Notting Hill Carnival. In which ways does your work centre on community?

SV:

Our forms of articulation are limited – we can only see and think through what’s possible with the language we have to articulate it. Once we expand on that language, we can produce entirely different worlds. Architecture is also, of course, a language. It is an abstraction, it has a set of codes, and it also communicates to us who we are. It affirms our place in the world in terms of what we deserve. We see ourselves in our surroundings and then we’re in conversation with those surroundings and we evolve them. That’s why representation and a manifestation of our identities in design are so important because we are in dialogue with it. We need slower forms of practice around what manifesting identity can look like, or can be, in architecture.

Responding to the historical erasure and scarcity of informal community spaces across London, Counterspace references and pays homage to existing and erased places that have held communities over time and continue to do so today. Among them are some of the first mosques built in the city, such as Fazl Mosque and East London Mosque, cooperative bookshops including Centerprise, Hackney, entertainment and cultural sites including The Four Aces Club on Dalston Lane, The Mangrove restaurant and the Notting Hill Carnival.

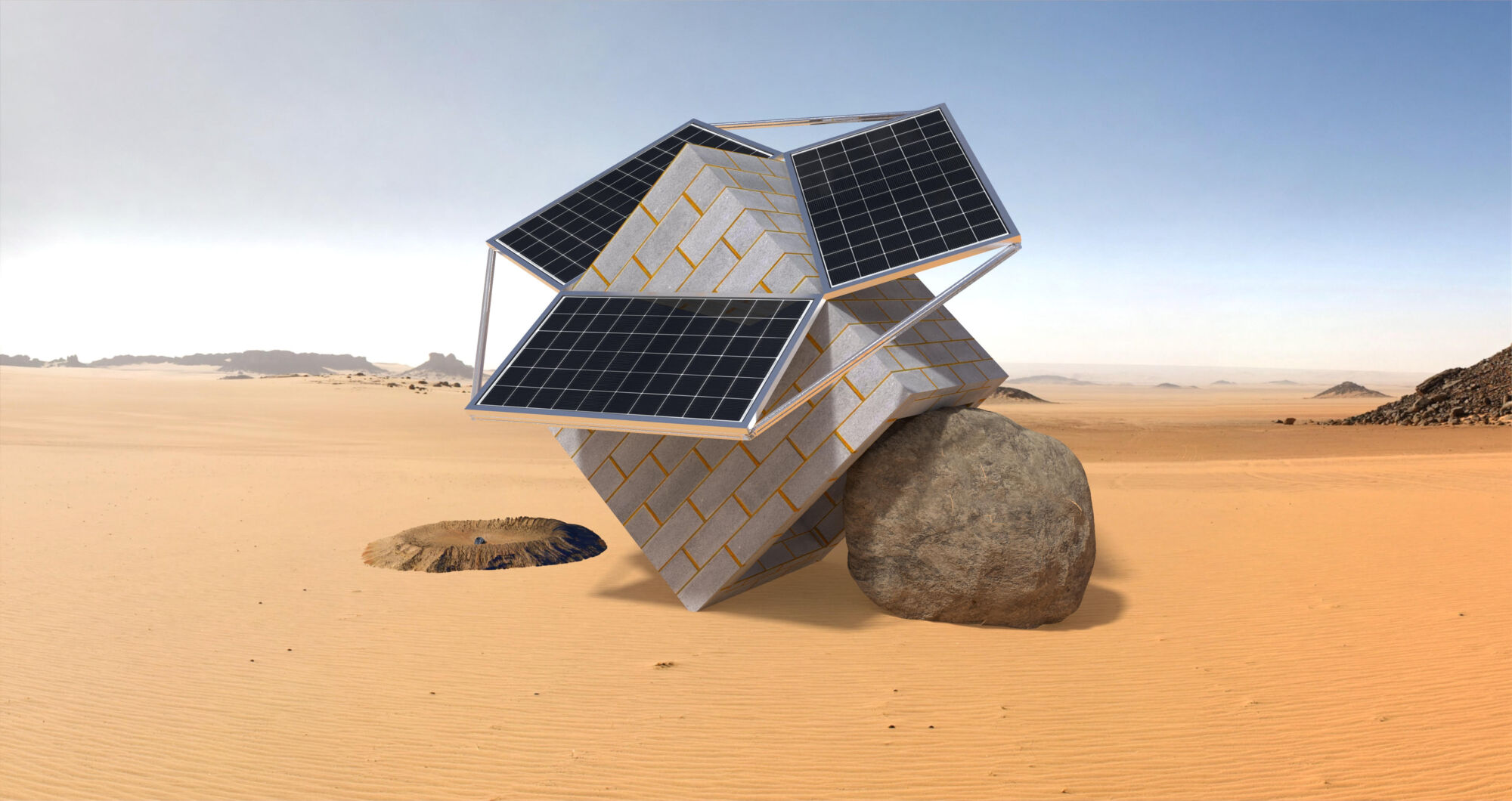

The Notting Hill Carnival Pavilion 2022 project grew from Sound System Sundays at The Tabernacle venue in Notting Hill – the live programme explored Counterspace’s interest in the history and architecture of sound systems in the UK and featured six sound systems selected with artist Alvaro Barrington and director of Notting Hill Carnival Matthew Phillip. The Pavilion is a small gesture (or offering) towards honouring the elders of Notting Hill and the origins of the resistance movements associated with Notting Hill. The project also took the form of a procession, a structure which comes together in parts. Community members placed the final pieces of the pyramid-shaped pavilion – seen as a work in progress – to make it complete. This project is so much about the process.

Through Support Structures for Support Structures, we are working to deepen the Pavilion’s intent and focus through a fellowship that helps nurture the practice of individuals and collectives that hold space for communities to gather across London. This fellowship truly gives us the opportunity to expand the reach of the Pavilion beyond its physical lifespan; and points directly to our collective role and the responsibility that architects have in working towards systemic change.

Inspired by the IsiZulu proverb ‘Oletha imvula uletha ukuphila’ (They who brings rain, brings life), the Pavilion for the Dhaka Art Summit (taking place at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy from 3-11 February) is a response to the local context and draws cultural parallels with the importance of rain in Bangladesh as the most important catalyst for agricultural production in the country. Wielding the comings of rain is a tradition practised by cultures across geographies. To possess the power to command rainfall is by inference possessing the power to dictate the flow of the natural cycle and climatic conditions. Across Southern Africa, rain-making rituals are directed towards royal ancestors as they were believed to have control over rain and other natural phenomena. One of these rare and powerful individuals is the Moroka of the Pedi tribe in South Africa. Moroka means the traditional rain-making doctor. Clay gourds and pots are assembled to form a temporal space formed by fired and unfired clay pots. Over the course of the installation performances drawing on the traditions of rain-making and harvest will be hosted in the space. These rituals include the use of water, dissolving the unfired pots to reveal areas and niches of gathering contained by the fired pots. A calendar of events, performance and maintenance is marked.

“Seeing the Biennale come to life through the voices and perspectives of our artists has been profound.”