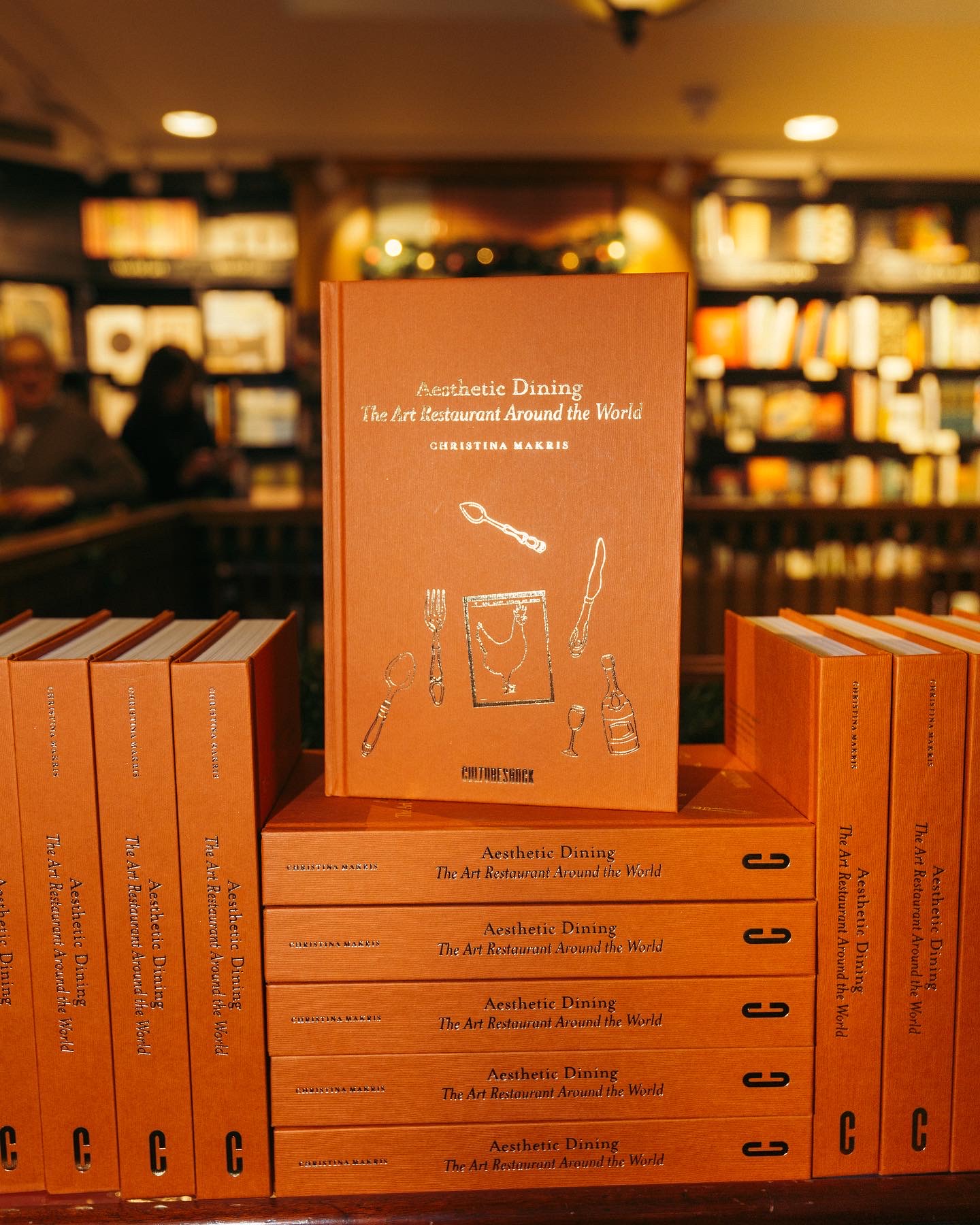

Interview Author Christina Makris

Following a career in academia, earning a doctorate in philosophy from Sussex University, Makris became involved in the arts as a collector, philanthropist and trustee, and with restaurants as an investor, consultant and sybarite. After noticing several restaurants displaying museum-worthy art, she began to explore the connection and meet the artists, restaurateurs and chefs in more than 20 of the world’s greatest art restaurants, from New York to Hong Kong and Cairo to London, to share the stories behind them. Here, she shares some of her favourite findings and the art and restaurants that excite her the most…

THE WICK: Talk us through a typical Monday

Christina Makris: If you love what you do for a living and have control over your time, weekdays and weekends are immaterial, and you keep schtum about workload. I don’t have typical days, but I do have typical habits. Every Monday begins with a daybreak run around Hyde Park – I stop for coffee on Seymour Place in Marylebone, then home to get ready. The week is always planned, so there is the first morning markets call of the week with colleagues of an investment fund I advise on. Monday lunchtimes are always a lunch meeting to see people I am working on my various projects with, be they from art or finance, as sharing ideas around the table is conducive to doing good business, or ‘hunger thinking’ as Ernest Hemingway called it. I’ve had a mixed career across different sectors, so am very comfortable working on different projects and in very different industries. Mondays can often be the quietest days in restaurants, so I tend to have an early dinner out to try a new place and catch up with a different friend every week tête-à-tête.

TW: As a self-described ‘restaurant philosopher’, where does your love of food and restaurants come from?

CM:

I am Greek, so we are overfed from the day we are born. Some of my earliest childhood memories are in restaurants, where we’d be taken several times a week, and always dressed up, so these places were always instilled with a sense of occasion and reverence, like a theatre or temple. If you think about it, those metaphors are how we experience restaurants anyway – there is a backstage bit (the kitchen) and the frontstage bit (the dining floor), where all the excitement unfolds for the delectation of the audience. We automatically play our roles in this drama when we go to restaurants without even knowing it; gossip, conversation, people watching, savouring the food, it’s all part of the performance.

I believe restaurants are important cultural creations. The best ones are creative endeavours, even a work of art in themselves, and certainly a cri de coeur of the chef who must share their passion with diners. Dining in a good restaurant is the second most pleasurable activity we can do. The restaurateur Ivor Braka says, ‘a restaurant should be somewhere you take someone you want to sleep with!’ and Peter Langan called himself ‘a culinary pimp’. I agree with these sentiments in terms of a good restaurant being somewhere you go to indulge the senses, to experience desire and satiation. Add in the right wine, the right conversation, and the pleasures of the table are yours for the taking.

TW: How do you define an ‘art restaurant’, and how did you select the restaurants that are featured in your book?

CM:

A book on art collections in restaurants had never been written before. Art in the dining environment, and all the theoretical discussions and aesthetic topics around it, raises some great questions on how we appreciate food and appreciate art, so I decided to ‘write it out’ and explore it.

An art restaurant is a place you visit to experience taste in two ways: literally and metaphorically. Taste the tongue and taste through the eyes, if you like. These restaurants in the book have different types of art in them – from chefs who collect art, restaurateurs who promote the arts, and artists who make works for restaurants. It’s not exactly just getting in the interior decorator to refurbish the place. The best restaurant art collections have grown organically. They are testaments of friendships between artists and chefs, they are another way chefs share their taste, and in some cases, happy accidents when artists just start coming to the place and bring other artists with them, like Lucio’s in Sydney or La Colombe d’Or in Provence before that. I identify a tradition that’s actually over 100 years old.

There is a strong affinity between chefs and artists – they can’t leave each other alone. It is possibly something to do with combining ingredients, provoking the senses and just good-natured sociability. Several artists, from Peter Blake to Michael Craig-Martin, Vik Muniz, Tracey Emin, Julian Schnabel and Damien Hirst among others, very kindly gave their thoughts for my book on where they eat, shared restaurant memories, and why they make works for restaurants, so it’s stuffed full of their anecdotes and stories, which helped me with my thinking on the topic.

TW: If you had to pick one art restaurant that should be on everyone’s must-dine list, what would it be?

CM: It is difficult to pick a favourite, because each one is unique and important in its own right. For instance, Dooky Chase’s in New Orleans is an incredible story. The young chef Leah Chase took over her in-laws’ family restaurant in the 1950s. She had an eye for art as well as a taste for traditional Creole comfort cuisine, so throughout the 50s and 60s she would let African American artists come to the restaurant and hang their works on the restaurant walls; Jim Crow and its immediate aftermath made it impossible for these artists to display in conventional galleries. She befriended many artists who turned out to be some of the most significant African American artists of the 20th Century: Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, Mel Andrews – all exchanged work for her food. Catlett was quite partial to Miss Leah’s fried shrimp, apparently. Chase also lent the restaurant to members of civil rights meetings in secret. She became a folk hero in the US; Tiana in Disney’s The Princess and the Frog is based on her, she fed the Bushes, she fed the Obamas (admonishing Barak for putting extra sauce on her gumbo). When I met her, she was 94 and still in her kitchen in her trademark pink apron giving me cooking and relationship tips (half of it I listened to). So Dooky Chase’s restaurant is an astonishing example of how restaurants have been important backdrops to culture and history.

“There is a strong affinity between chefs and artists – they can’t leave each other alone.”