Interview Lakwena Maciver, Artist

A firm believer that art should be accessible and enjoyable, she’s best known for her Instagram-worthy murals. Utilising a combination of words, kaleidoscopic colours and bold patterns, her work, which has appeared in public spaces from London’s Tate Britain to a juvenile detention centre in Arkansas and a monastery in Vienna, explores ideas relating to decolonisation, redemption and escapism.

As well as recently taking over Somerset House’s courtyard and West Wing corridor for the 2021 edition of the 1-54 Courtyard Sculpture Commission, she has also transformed the concrete roof terrace of Temple tube station with a technicolour art installation. Before you rush off to Temple to see ‘Back in the Air: A Meditation on Higher Ground’, which is on show until April 2022, you can discover Lakwena’s thoughts on public art and being an artist and a mother below.

THE WICK: Talk us through a typical Monday.

Lakwena Maciver: Get woken up by the kids. Lie in bed as long as I can. Get ready. Ride to the studio. Go through emails. Work out what needs to be done for the day. Do it. Go home.

TW: You’ve transformed the rooftop of Temple Underground Station with a rainbow of geometric forms. How do you see this public work fitting into the fabric of the city?

LM: I actually see it as an intervention, breaking up the concrete and greyness of the city. Not so much fitting in as breaking up the city.

TW: What inspired your works for this year’s 1-54 Courtyard Sculpture Commission?

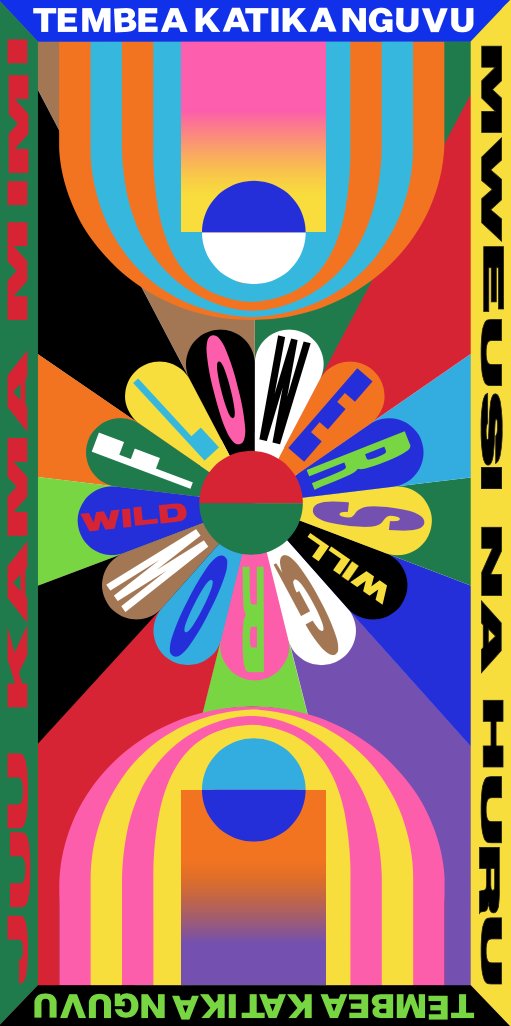

LM: Lots of things. Flowers. Wildness. Paying my respects. This series of works began when I was invited to make an artwork for a basketball court in Arkansas. I’d recently watched this viral video of Senator Flowers of Arkansas raging against stand-your-ground laws and was really inspired to make something that would honour her, but also speak about rising up. So, it was beautiful timing. Then when this opportunity at 1-54 came up, it felt like a good fit for that. I was thinking about the significance of Somerset House as a historical site, and I was playing with this idea of the courtyard being a garden, where games might be played and where wildflowers might grow, in contrast to having a very manicured lawn with signs up saying ‘no ball games’. That’s where basketball and flowers come in. Probably an unusual mix, but it all makes sense to me. I like how universal basketball is – that it is accessible. Also, that it’s a game dominated by African-diaspora men. It is a beautiful expression of black male joy.

TW: How does the location of your installations influence your approach?

LM: I really like to respond to a site rather than just put something random in it. I like to research a space and weave a story into/out of it. My recent intervention at Temple Station is a good example. Even just the name of the site had so much potential to be played with.

“I like to research a space and weave a story into/out of it.”