Interview Artist and Photo London’s 2024 Master of Photography Valérie Belin

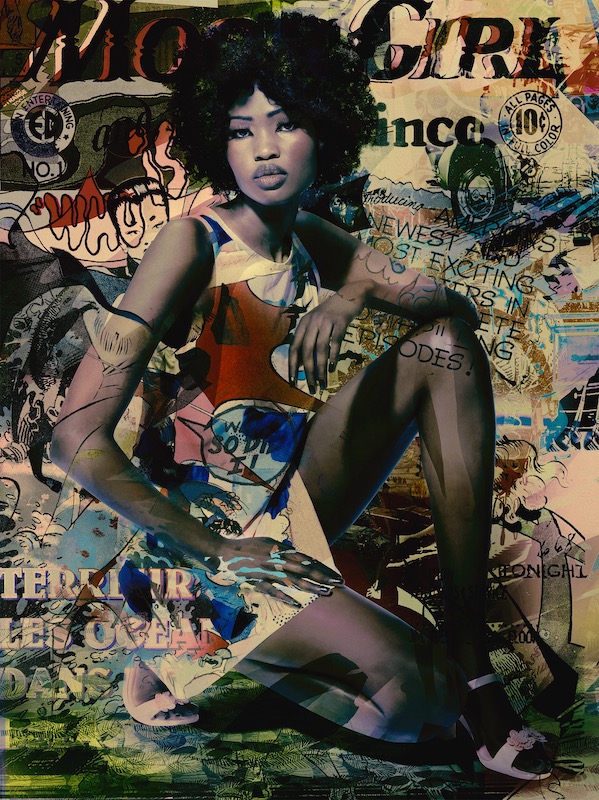

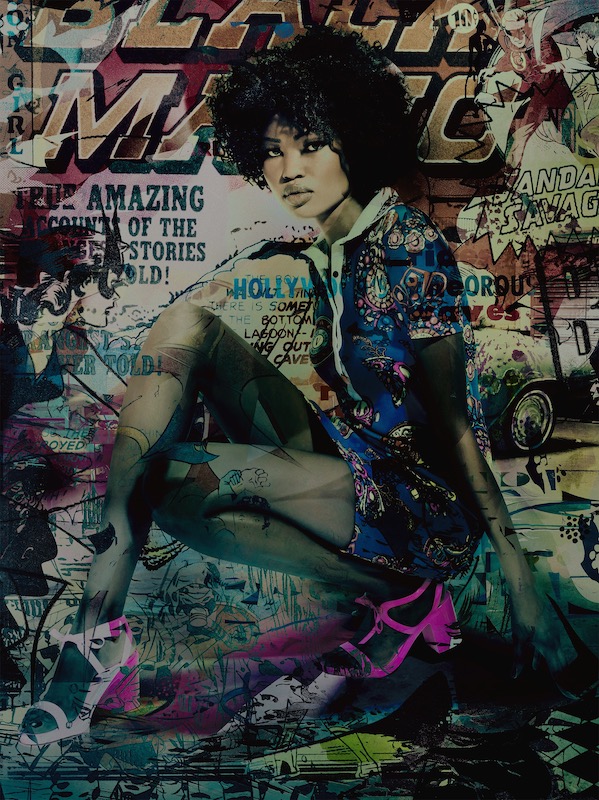

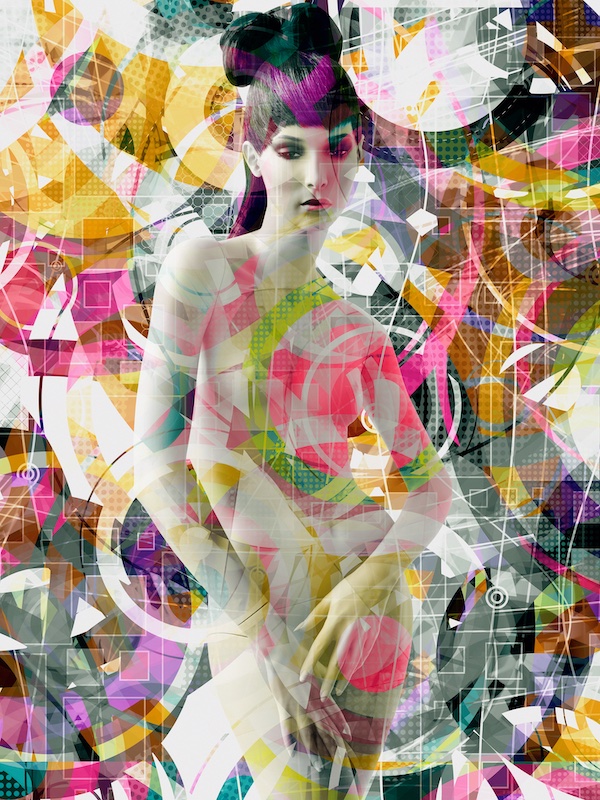

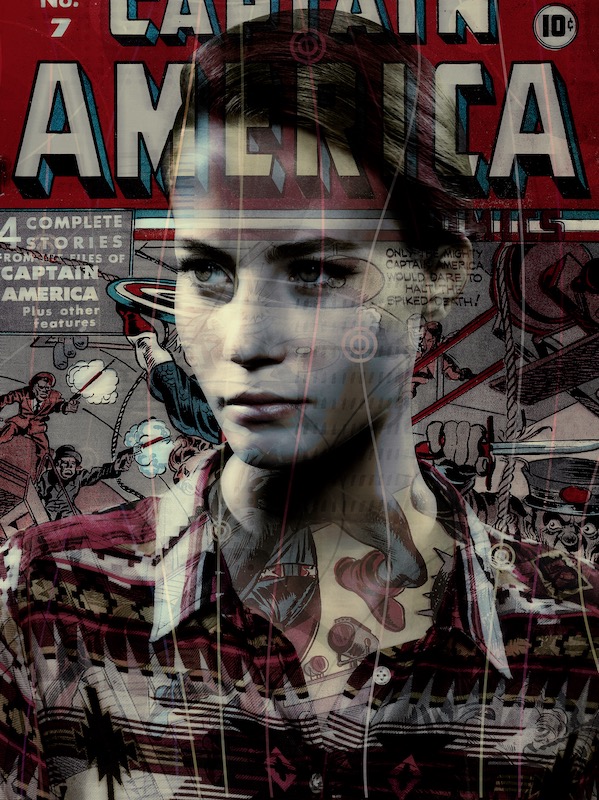

Over the thirty years Belin has been active, her works have focused on body builders, car crashes, fashion models, Michael Jackson look-alikes and card sharks, always exploring the plasticity of bodies and photography’s ability to create artifice and illusion. Sometimes surreal, often disquieting, Belin’s uses digital technologies to achieve the eerie effects of colour and texture that are a signature in her work, distancing familiar imagery even further from our perception of what is ‘real’.

Awarded the Paris Photo Prize in 2007, the Prix Pictet in 2015 and the prestigious Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2019, Belin’s works have been exhibited all over the world and belong to numerous major collections – including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, and the V&A Museum, London, to name a few. Ahead of this landmark moment in her three decade-long career, Belin answered The Wick’s questions, telling us more about the conceptual linchpins behind her arresting images, what the accolades mean to her – and why she’s pining for a photograph by Walker Evans.

THE WICK:

You have just opened a major solo exhibition in France, with works from a number of important series. Can you tell us more about the exhibition and what it reveals about your practice?

Valérie Belin:

It’s a solo exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, running from April to October 2024. It’s a retrospective of my work from the mid-1990s onwards, including the latest series of photographs I’ve made. The exhibition is in two parts: a major monographic exhibition, spanning all three floors of the gallery, and around ten photographs presented in relation to works from the museum’s permanent collection. This exhibition provides a better understanding of the nature of my work, and in particular the link between my practice of photography and painting.

TW:

What made you initially interested in creating photographs that blur “real” and “illusory”?

VB:

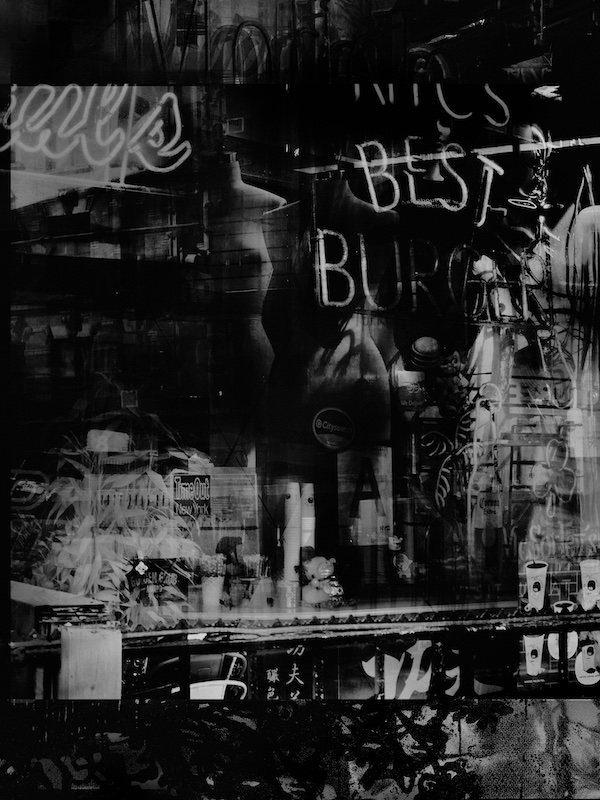

I became aware of the “fake” nature of photography very early on, for example when I photographed glass objects and mirrors. This became obvious when I photographed the bodies of bodybuilders. I went on making photographs of models, transsexuals and look-alikes that questioned notions of identity and gender. Then I ended up making hyper-realistic portraits of window mannequins where you’re not quite sure whether what you’re seeing is real or fake. I think that photography, like painting, is an artefact. It doesn’t represent reality; there’s a gap between what you see and what is really there. The real subject of my photographs lies in this slight discrepancy.

TW:

You have also considered the ways in which notions of gender and identity as a performance – how has this evolved in your work?

VB:

I became interested in these issues when I took portraits of trans individuals in their transitional phase, and also when I took portraits of Michael Jackson lookalikes. This desire for transformation in the people photographed was a form of existential performance. It gave me the idea of turning it into an artistic performance in itself, which was presented at the Centre Pompidou in 2013.

TW: What kind of sources do you use for creating your work?

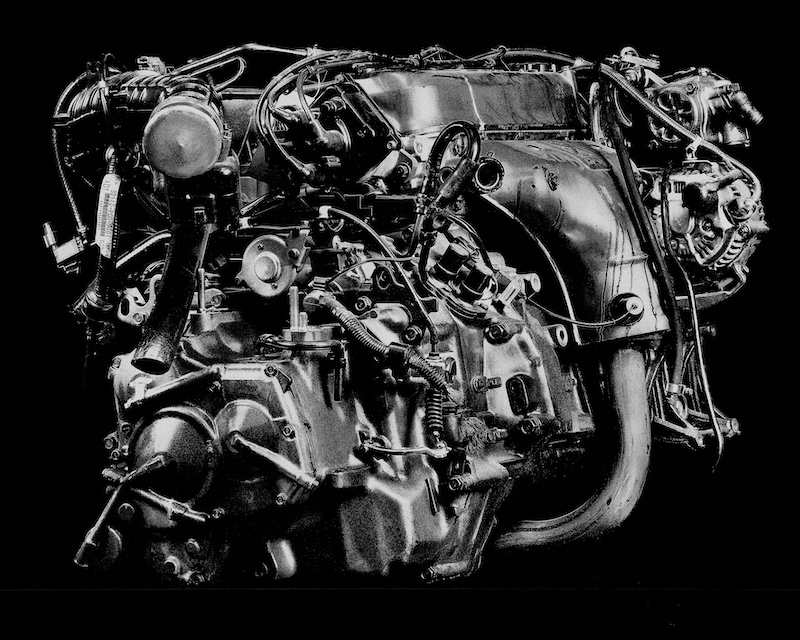

VB: I draw my inspiration from many sources: literature, film (Hitchcock’s films, for example), magazines, photography, painting… In 2002, when I took photographs of engines that can be considered as “still lifes”, I was inspired by Agnus Dei, a painting by Francisco de Zurbarán that can be seen in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

“Think of your work as a matter of life and death.”