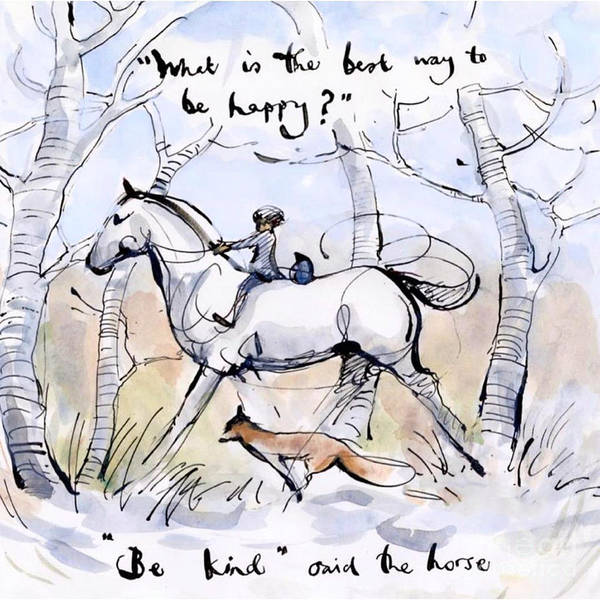

Discover Charlie Mackesy, What is the best way to be happy

It’s hard to think of a British artist of more touching scenes than Charlie Mackesy. His endearing drawings of four unlikely friends, the boy, the mole, the fox and the horse, accompanied by life-affirming words and phrases, have earned him an adoring public the world over. Many have sought comfort and solace in his uplifting messages of love and friendship. But why does his work resonate so widely? ‘The world is complicated and quite frightening and there is a simplicity to it perhaps,’ he has said. Added to this is his refreshing outlook on what constitutes success. ‘To me the [greatest] achievement is to love and be kind. It’s so rarely seen as success, but I think it is.’ This gorgeous illustration is testament to Mackesy’s heart-warming vision. Share or save immediately.

Share