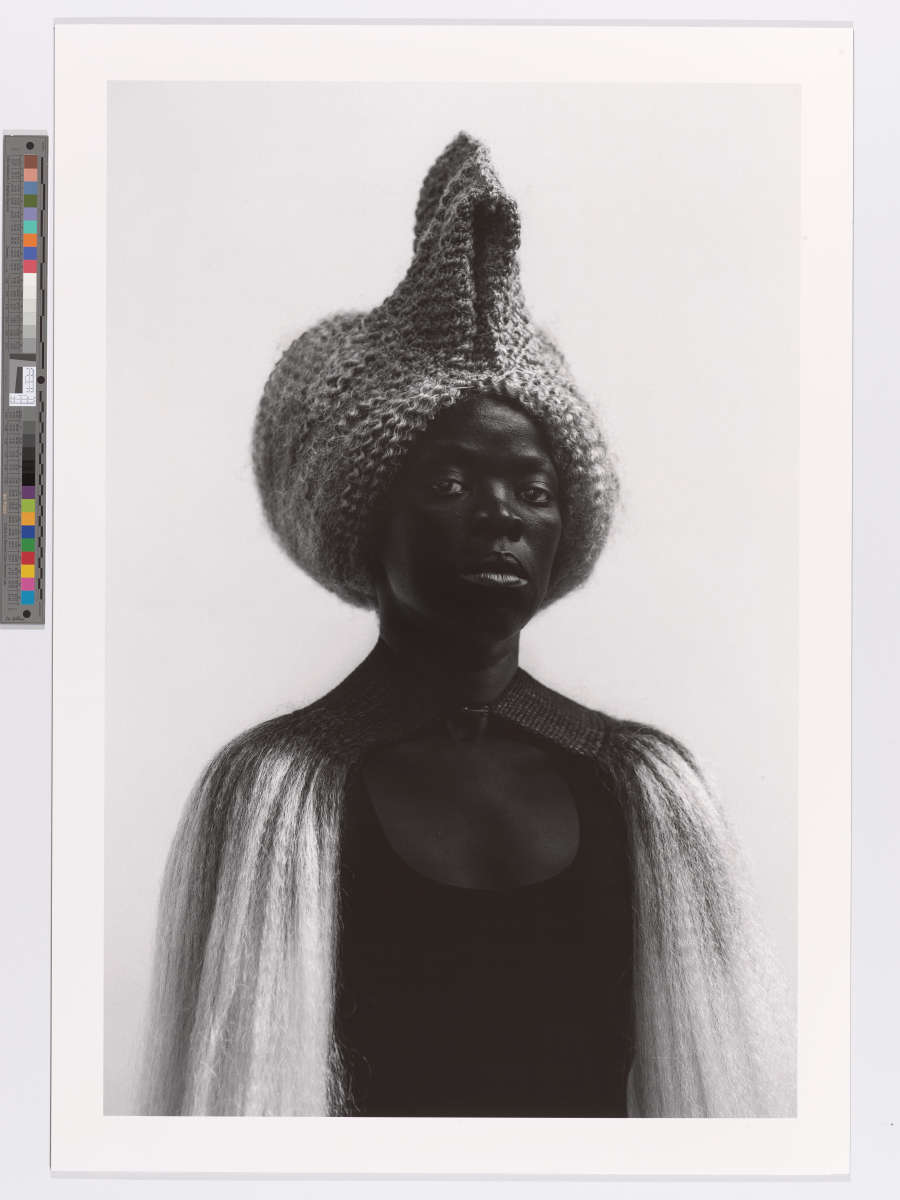

Discover Kalibbala from the Kuchu Nsenene (Grasshopper) Clan, 2023-2024, by Leilah Babirye

As we continue to honour contemporary queer artists through Pride Month and beyond at The Wick, we look to the woven, whittled and welded sculptures of Ugandan artist Leila Babirye. Babirye was forced to flee her home country in 2015 after her sexuality was revealed in a local newspaper. The Ugandan Parliament had since passed the Anti-Homosexuality Act in March 2023, criminalizing consensual same-sex conduct with penalties of up to life imprisonment, and the death penalty for those convicted of “aggravated homosexuality,” which includes repeated same sex acts. LGBTQI people face widespread, endemic violence and discrimination. In 2018, Babirye was granted asylum in the US.

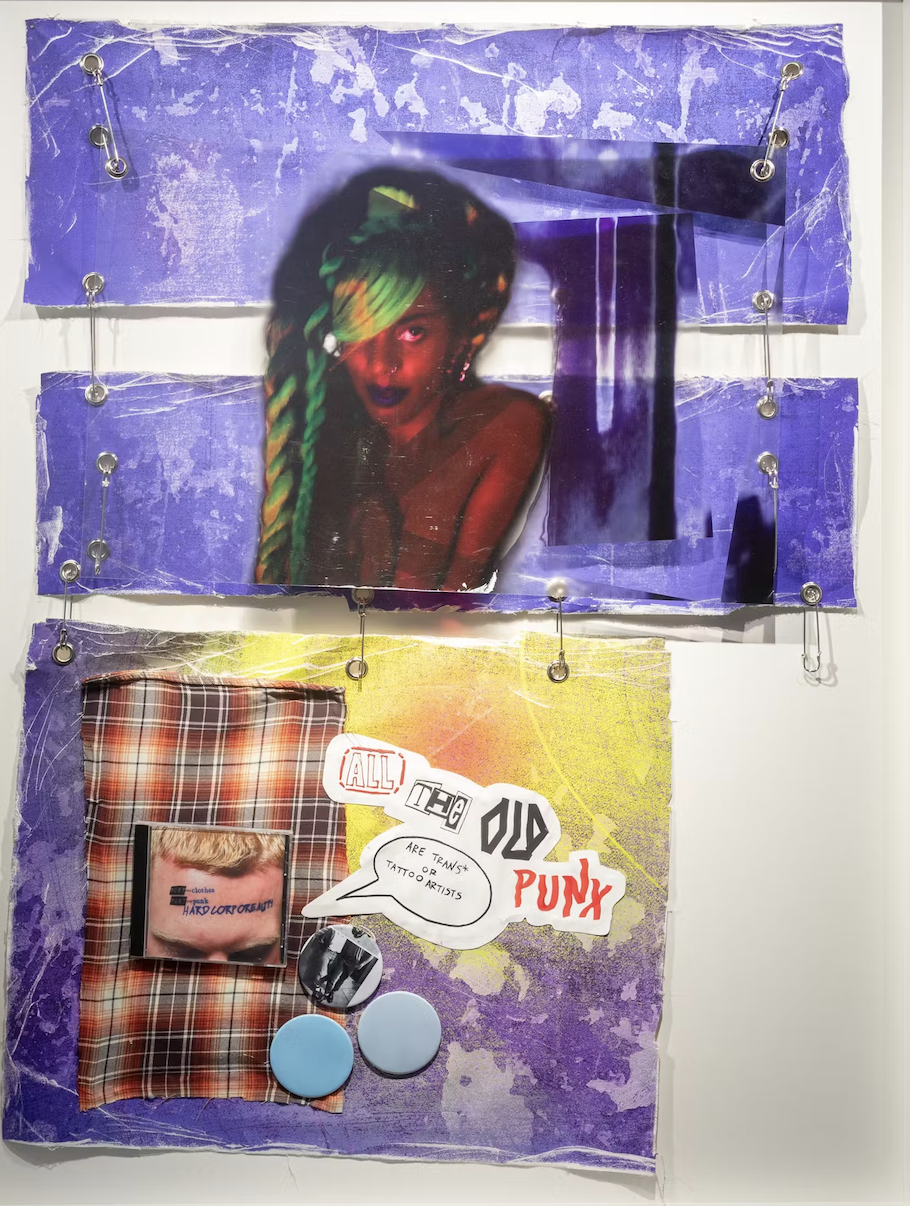

In her adopted home of New York, Babirye collects discarded items from the streets, transforming these unwanted items into defiant objects of beauty. Traditional African masks, hand carved in wood or cast in clay, are incorporated into her sculptures too, representing the diverse community she lives among – such as this vibrant piece constructed of glazed ceramic, wood, wax, bicycle tubes and found objects, nailed together into a totem that appears both strong and fragile.

Describing her process, Babirye explains: “Through the act of burning, nailing and assembling, I aim to address the realities of being gay in the context of Uganda and Africa in general.”

In her adopted home of New York, Babirye collects discarded items from the streets, transforming these unwanted items into defiant objects of beauty. Traditional African masks, hand carved in wood or cast in clay, are incorporated into her sculptures too, representing the diverse community she lives among – such as this vibrant piece constructed of glazed ceramic, wood, wax, bicycle tubes and found objects, nailed together into a totem that appears both strong and fragile.

Describing her process, Babirye explains: “Through the act of burning, nailing and assembling, I aim to address the realities of being gay in the context of Uganda and Africa in general.”

Share